Yesterday, for the first time in about a year, I played Bit Pilot. It's an astonishingly good game, and I found myself pondering what qualities made it fun. Games aren't made via checklists, of course. You can't take these elements, tick them off, and expect to have a fun game. There's also a standard disclaimer. But that doesn't mean we shouldn't try to learn from the work of others. So, why is Bit Pilot fun?

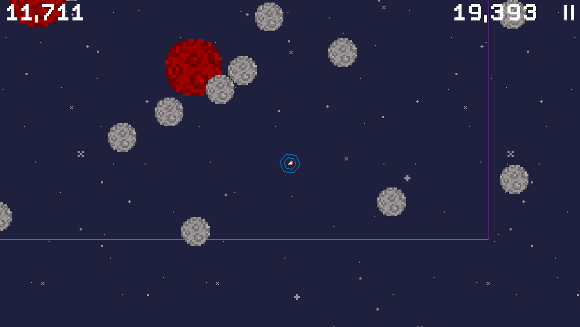

Bit Pilot has a simple concept, well-executed. You control a spaceship in a restricted playing area. Dodge the asteroids and laser beams. Collect power-ups if you can. That's it: there's no sprawling back-story, no giant sandbox, no growling beefy protagonist. Just you versus the game – and you will always lose. There's also no victory screen: you're pitted against your own prior performance (your high score) and any friends you can persuade to play too. This simplicity is an attraction. But a simple idea, no matter how elegant, isn't going to make people play for hours unless there's something more at work.

Balancing a chair on two legs

You're sitting at a desk and you push yourself away from it and now this four-legged chair is balanced on its two hind legs and you. are. awesome. We've all delighted in that, right? There's two unconscious thoughts that ping-pong back and forth while you're doing this:

- I'm so skilled. Check out my goat-like balance. This is ace. I'm ace.

- WHOA FUCK I ALMOST LOST IT phew I'm fine

It's this interplay that Bit Pilot replicates. Most of the time you feel in control and impressed with your abilities, but there's these little nudging pokes that knock you off balance. It's not a stable system; sometimes you'll get away with it, but in the end you'll lose. You come back for more because of the times you get away with it, and because the feeling of control is so addictive.

Pushing your boundaries

The reason you always lose is because Bit Pilot gently but constantly pushes on your boundaries. The special asteroids and laser beams are part of this, but the main pressure is the asteroids becoming bigger. Over time there's less space and more asteroid. You can't win; eventually there'll be no space left.

Super Hexagon is another game that got its hooks into me. It's difficult in a different way; it's far more overwhelming at first1. There's so much happening on-screen it's hard to grasp what's happening. And just when you start to get a grip, the game speeds up, or reverses direction, or introduces a new obstacle. Super Hexagon doesn't give me the same balanced-on-a-knife-edge feeling, though maybe I've played it too much. When I die in Bit Pilot, I think "I should have avoided that." When I die in Super Hexagon, I think "Yeah, you got me." Infinite runners like Canabalt have the purest implementation of this: they speed up the longer you play, giving you less time to react.

A balanced difficulty curve

Some games don't forgive mistakes. Super Hexagon and Canabalt both have instadeath: one mistake and you die. Other games give you lives. Bit Pilot has a lives system – your ship starts with two shields, and you can accumulate more – but it's more effective than your standard 3-lives-then-game-over mechanism.

There's no penalty for losing a life – no going back to the start of a level or losing your power-ups. The graphics and sound tell you you messed up, but there's no immediate consequence beyond feeling more exposed than before. You can also pick up extra shields, until your ship is nestled in the centre of a giant hexagonal onion. But it gets harder and harder to keep them: the more shields you have, the bigger you are. You can't slip through tiny gaps any more. Conversely, you become a smaller target as you get closer to death. The stakes are higher, but the odds are more in your favour.

No time to reflect

A key hook in both Super Hexagon and Super Crate Box is keeping the time between "game over" and "new game" as short as possible. One quick reflexive tap and you're back in the action. No time to think about the previous game; stay in the zone, and keep playing. It's not a case of thinking "Just one more go." It's a case of not thinking at all.

Perfect controls

A game has perfect controls if you never think about them. Bit Pilot has a neat two-thumbs method that is a devil to explain, but it feels fantastic. Essentially, your two thumbs sum together. You can't understand it without playing the game, but it enables tiny intricate moves as well as big sweeping manoeuvres. You won't make many of those, though; part of its appeal is that (despite the fast pace) it's a game of subtlety. You'll die quickly if you pinball around the screen. Patiently wait in the middle, though, and make small adjustments... you'll live a little longer.

Super Crate Box, by contrast, has infuriating controls2. PC to touchscreen ports are always hard because on-screen buttons suck. Around 50% of my Super Crate Box deaths are down to a lack of control; things going awry between my fingers and the device. I end up jumping when I meant to shoot, shooting when I tried to jump, my jump going awry. It's frustrating, and it never happens in Bit Pilot or Super Hexagon. The chair-balance feeling depends on creating a feeling of mastery; you can't get that if it doesn't feel like your avatar3 obeys your commands.

Making it happen in your own work

I'm not a game developer, so I can't tell you how to build the perfect controls or chair-balancing feeling into your own games. I suspect it's art, not science; tweaking and playtesting until it feels right. I never got obsessed by Canabalt, but the developer spent a lot of time tweaking it until it played well.

And if your game lacks these qualities, don't worry. These principles aren't universal. Plenty of great games are made of different elements. There are games I love that are story-driven, or subverting the form, or wonderful art, or are simply absurd. But if your game lacks tension, excitement, and stickiness, think about whether you're lacking that chair-balanced-on-two-legs feeling.